- Heat flow is altered within the chip components rather than being removed after buildup.

- Phonon motion is constrained by nanoscale surface patterns

- Ultrafast lasers make it possible to create nanoscale patterns at industrially relevant speeds

Today, most electronic products rely on heat sinks, fans, or liquid cooling because the components inside the chips conduct heat in a fixed manner.

A new method designed by Japanese researchers allows engineers to control how quickly heat escapes from a material, rather than simply trying to remove heat after it builds up.

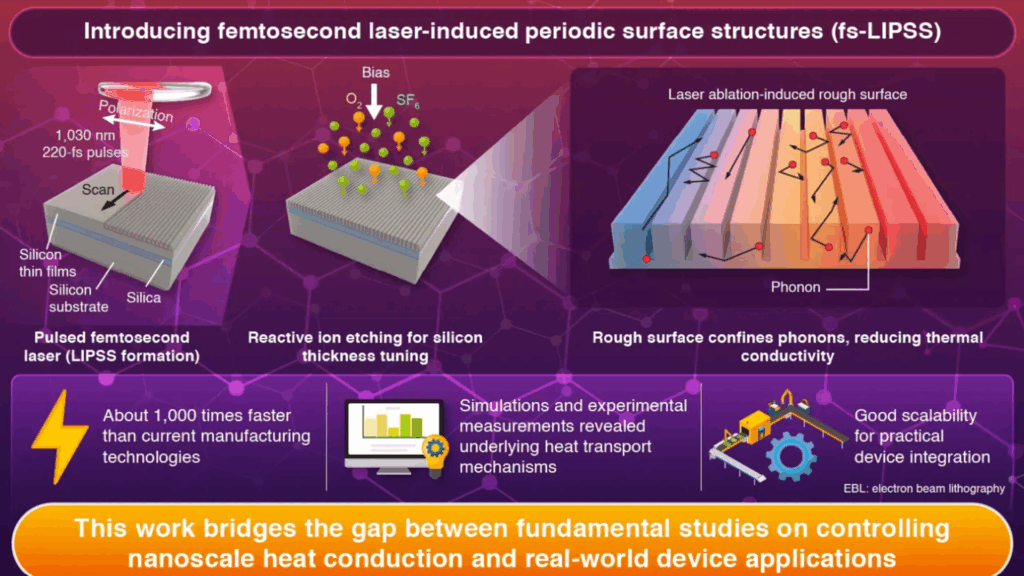

The work describes a laser-based manufacturing method that modifies the way heat moves through thin films of silicon and silica by directly shaping their nanoscale surfaces.

Alteration of heat transport at the level of chip components

The approach relies on ultrafast laser pulses, each lasting one femtosecond, to ablate material and create parallel grooves on the film surface.

These grooves form with a carefully controlled spacing and depth that closely matches the average distance that phonons travel before scattering.

Because phonons are the primary heat carriers in these components, restricting their movement unsurprisingly alters the overall thermal conductivity.

The resulting features, known as femtosecond laser-induced periodic surface structures, show high uniformity over relatively large areas.

When combined with conventional dry etching to adjust film thickness, the patterned surfaces exhibit a marked reduction in thermal conductivity.

Thermoreflectance measurements quantified this change and provided experimental confirmation rather than inferred behavior.

Numerical simulations also showed that the reduction arises primarily from limited phonon travel distances rather than from changes in the chemical composition or properties of the bulk material.

A central claim of the study refers to the speed of manufacturing. The fs-LIPSS process is reported to operate at a throughput more than 1000 times faster than single-beam electron beam lithography while achieving nanoscale resolution.

This difference is substantial, especially for applications that require large patterned areas, such as thermal layers built into data center-class processors.

The process is mask-free and resistor-free, reducing procedural complexity and aligning with standard CMOS manufacturing constraints.

The technique has also been described as capable of being implemented at wafer scale without introducing additional components or lithographic steps.

Because the method avoids resistors and masks, it remains compatible with established semiconductor workflows.

The researchers describe the process as scalable, semiconductor-ready and suitable for integration with existing manufacturing lines.

The nanostructures are described as mechanically robust, with reports indicating strength levels up to 1000 times higher than those produced using some conventional patterning approaches.

However, the available description provides limited details on direct mechanical benchmarking or comparative test methods.

The technique appears promising and is relevant to high-performance computing, quantum devices, and thermal management challenges associated with the dense clusters of GPUs that power modern AI tools.

But broader adoption will depend on reproducibility, long-term stability and cost under industrial conditions, especially at data center deployment scales.

Through Tokyo Institute of Science

Follow TechRadar on Google News and add us as a preferred source to receive news, reviews and opinions from our experts in your feeds. Be sure to click the Follow button!

And of course you can also follow TechRadar on TikTok for news, reviews, unboxings in video form and receive regular updates from us on WhatsApp also.