- Tungsten carbide can now be printed without melting or ruining its strength.

- A laser and heated wire soften the metal enough to bond layers

- Avoiding full melting reduces defects that previously blocked metal additive manufacturing

Most people are familiar with 3D printers that make plastic parts, toys, or simple tools, but printing metal is much more difficult.

The reason is that metals require extremely high heat and react poorly when heated and cooled too quickly.

However, in a breakthrough, scientists at Hiroshima University have shown that tungsten carbide cobalt can now be 3D printed using a different method.

Instead of completely melting the metal, the process heats it enough to soften it. This allows the material to be layered layer by layer without losing its internal structure.

The method uses a laser and a heated wire to soften a solid carbide rod during printing.

A thin layer of nickel alloy is also placed between the printed layers to help them stick together more reliably.

Because the metal is not completely molten, the printed result avoids many of the defects seen in previous attempts.

The researchers report that the final printed material reaches a hardness greater than 1400HV, without introducing defects or decomposition.

This level of hardness is only slightly lower than materials such as sapphire and diamond, which is unusual for 3D printed metal parts.

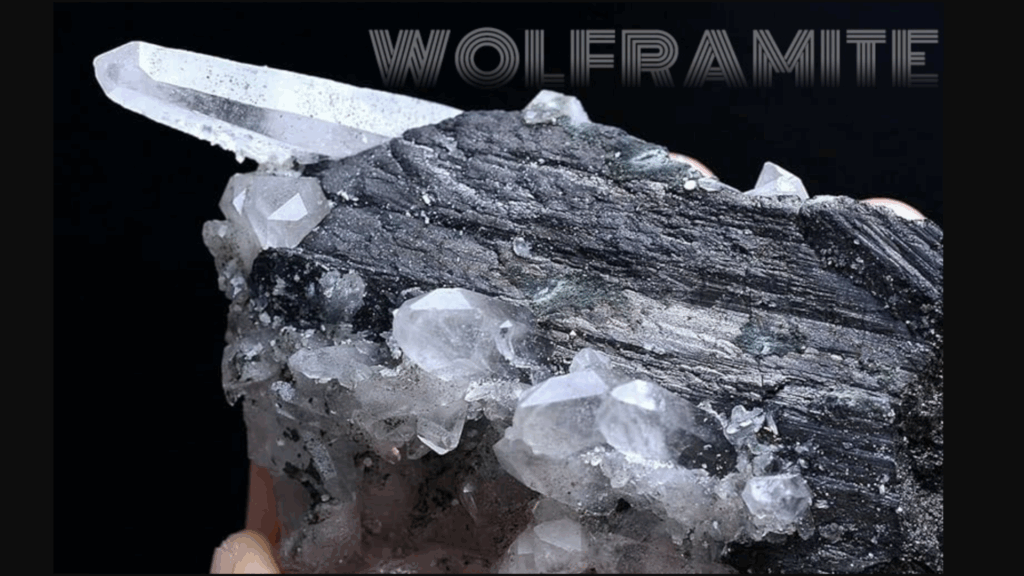

Tungsten carbide is widely used in cutting and construction tools, and is one of the hardest engineering materials in use today.

These tools are usually made by shaping solid blocks of material, which generates a large amount of waste.

Being able to 3D print defect-free industrial-grade carbides could reduce material waste and allow parts to get closer to their final shape.

The current process still has problems with cracking in some cases, and it is still not easy to produce complex shapes.

“The approach of forming metallic materials by softening them instead of completely melting them is novel,” said Keita Marumoto, an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering at Hiroshima University.

“It has the potential to be applied not only to cemented carbides, which were the focus of this study, but also to other materials.”

Despite the advances, this work does not mean that tungsten parts will soon be printed in everyday environments.

Metal printing is still slower, more expensive and harder to control than plastic printing.

Researchers say further refinements to the process are needed to reduce cracking and allow for more complex designs.

The idea of softening metals instead of melting them seems promising, but its real-world value will depend on whether it can be scaled, reliably replicated, and operated outside of test environments.

Through Tom Hardware

Follow TechRadar on Google News and add us as a preferred source to receive news, reviews and opinions from our experts in your feeds. Be sure to click the Follow button!

And of course you can also follow TechRadar on TikTok for news, reviews, unboxings in video form and receive regular updates from us on WhatsApp also.