My latest creation of notebook podcast is deeper and more fascinating than anything that has created, and I bet that it will also surprise you.

I do not understand strings theory. In fact, I bet that there is less than 1% of the world that can speak convincingly on the subject, but the concept fascinates me and I have read it a little. It is not enough to understand or explain it, but enough to have a constant and permanent curiosity.

AI, on the other hand, I think I understand and now use regularly as a tool. When Google launched a recent update of Notebooklm that includes, among other things, mental maps, I thought it was time to gather something at the outer edges of my understanding and this artificial intelligence of hemorrhagic edge.

Then I created a chain theory podcast.

First, a small primer in Notebooklm. It is a powerful research tool based on AI in which sources can load, and will make them summaries and extrapolated information in text, podcasts and visual guides such as mental maps.

For me, the most fascinating part has been the podcasts or “audio descriptions”, which produce Charlatans audio conversations about virtually any topic that feeds with them. I call it a podcast because the audio style walks a very used path of the most popular podcast series. It is conversational, generally between two people, sometimes fun and always accessible.

However, I have been wondering, if you can stretch the limits of the format with such a deep and, honestly, confusing issue that the resulting podcast would be conversational nonsense.

However, my experiment showed that while the current version of Notebooklm has its limits, it is much better to understand the dense science bits than me and probably most of the people you or I know.

Strange science

Once I decided that I wanted Notebooklm to help me with the subject, I went in search of string theory content (there is much more online than I might think), quickly stumbling with this research work of 218 pages of 2009 by the researcher at the University of Cambridge, Dr. David Tong.

I scanned the doctor and could say that he was rich with details of string theory, and so far on my head, he probably resides somewhere near Saturn’s rings.

Imagine trying to read this document and make sense. Maybe someone explained For me, I would understand. Maybe.

I downloaded the PDF and then fed it in Notebooklm, where I requested a podcast and a mental map.

It took me almost 30 minutes to Notebooklm to create the podcast, and I must admit that I was a little anxious when I opened it. What happens if this mass of details on one of the most confusing themes of physics overwhelmed Google’s AI? Could the hosts be unbalanced?

I shouldn’t have worried.

I had heard these podcast hosts before: a couple some vanilla (a man and a woman) who jokes coincidentally, while making an ingenious. In this case, they were trying to explain the strings theory to those not initiated.

They began talking about how they would walk on the subject, covering bits such as general relativity, quantum mechanics and how, at least 2009, we had never directly observed these “strings.” Earlier this month, some physicists affirmed that, in fact, they had found the “first evidence of observation that supported the string theory.” But I’m deviating.

The hosts spoke as physics experts, but, where possible, in terms of lay people. I quickly found myself wishing they had a guest. The podcast would have worked better if they were representatives for me, they did not understand much at all, and had an expert generated by AI to interview.

Chaining everything together

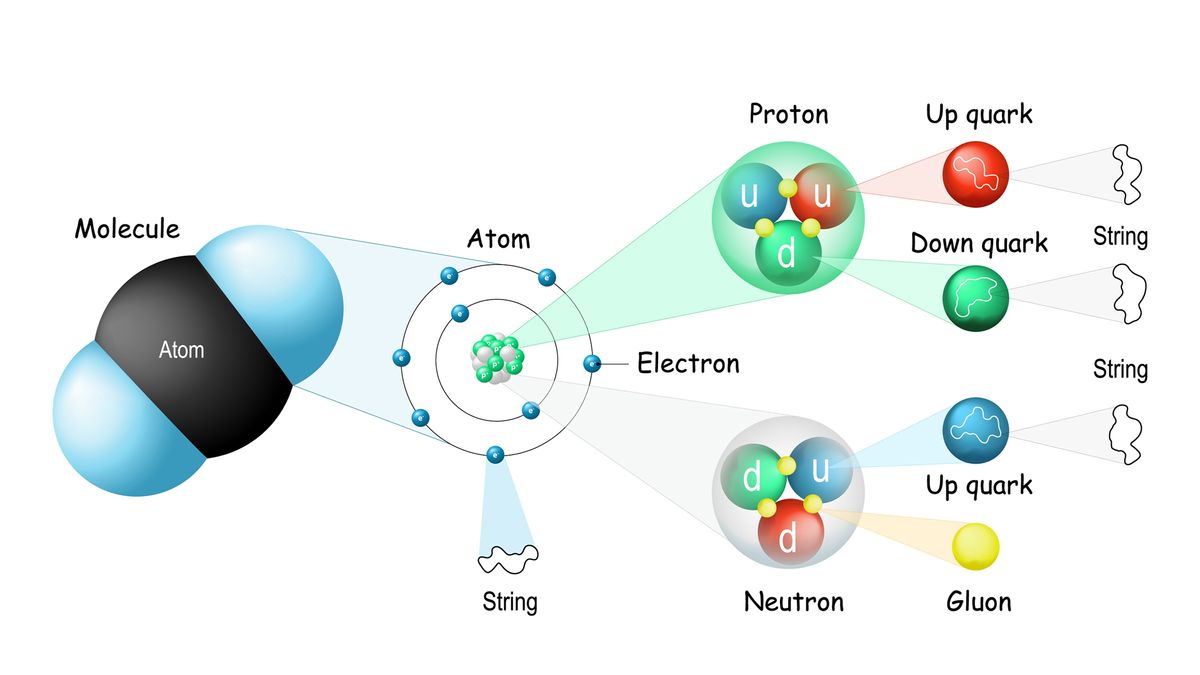

As the podcast advanced, the hosts excavated in the details of string theory, specifically, the definition of a “chain”. They described them as small objects that vibrate and added: “All things in the universe come from how small strings are vibrating.”

Things became more complex from there, and although the tone of the hosts of AI’s podcasts never changed, I had trouble following it. I still can’t tell him what he really means “the relativistic point particle seen through Einstein’s special relativity.” Although I appreciated the analogy of “imagine a rope that moves through spatial time.”

The hosts of AI used several tricks to keep me committed and not completely confused. The male host, as a podcast parrot, would often repeat a bit of what the female hostess had just explained, and would use some decent analogies to try to identify.

Sometimes, the female host expelled what sounded as if she were reading directly from the research work, but the male host was always there to withdraw it to the entertainment mode. He made a lot of talk.

I felt that I connected to everything when they explained how “the rope became the theory of everything” and added: “Bosons and fermions, partners in the crime due to supersymmetry.”

This was heavy

After 25 minutes of this, my head was full to the point of exploding with those strings still theoretical and turning with terms such as “vertices” and “holomorphic” operators.

I expected a great and glorious summary at the end, but the podcast ended up almost 31 minutes. It was cut as if the hosts ran out of flowers, ideas or information, and moved away from the microphones with frustration and without signing.

Somehow, it seems that this is my fault. After all, I forced these Sims to learn all these things and then explain to me, because I could never do it. Maybe they would be fed up.

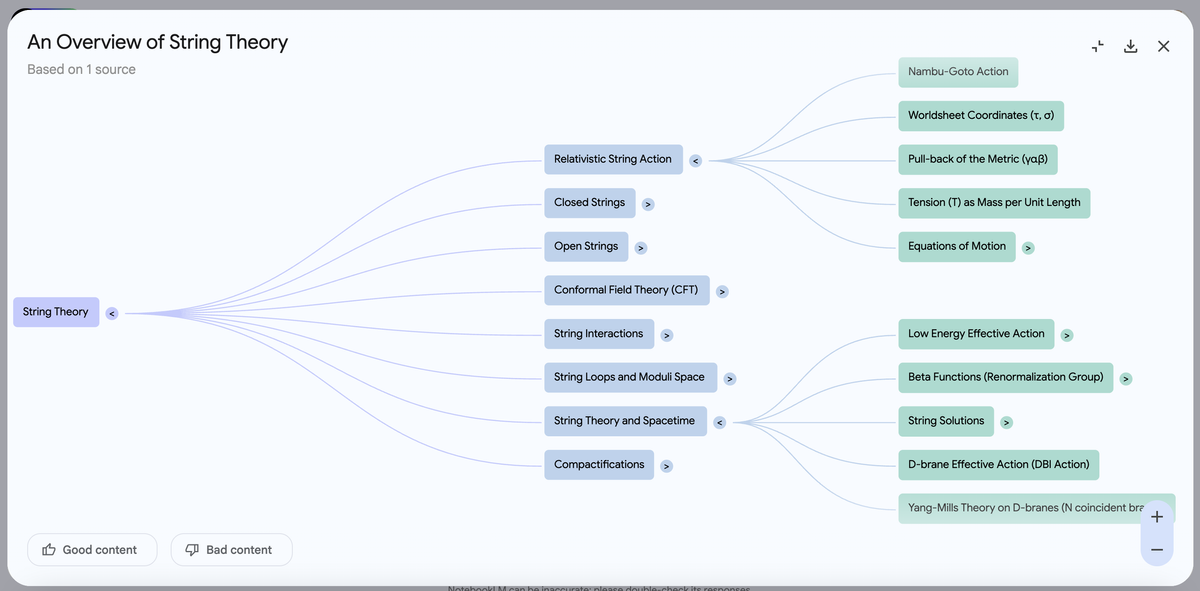

I also checked mental maps, which are branch diagrams that can help you map and represent complex issues such as string theory. As you can imagine, the maps for this topic begin simple but become increasingly complex as each branch expands. Even so, they are a good podcast studio partner.

It is also worth noting that you could enrich the podcast and mental maps with other sources of research. I would simply add them to the Fuentes panel in Notebooklm and return to execute the “general audio description”.

A true expert weighs

As much as I learned and, no matter how much I trust the source material, I asked myself about the precision of the podcast. AI, even with solid information, can hallucinate, or at least misunderstand. I tried to contact the author of the newspaper, Dr. Tong, but I never received an answer. Then, I resorted to another physics expert, Michael Lubell, professor of Physics at City College of Cuny.

Dr. Lubell agreed to hear the podcast and give me some comments. A week later, he sent me an email to this brief note: “I just heard the chain theory podcast. Curiously presented, but requires a reasonable amount of experience to follow it.”

When I asked about any obvious error, Lubell wrote: “Nothing obvious, but I have never done an investigation in string theory.” Quite fair, but I am willing to bet that Lubell understands and knows more about string theory than me.

Perhaps, the podcasters of AI now know more on the subject than any of us.