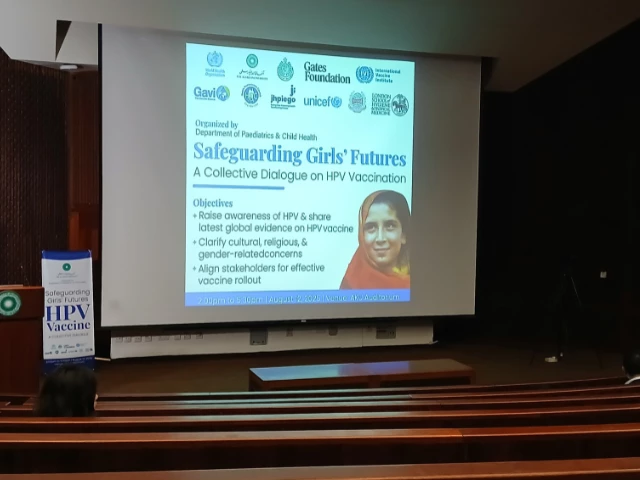

The Human Papilloma (HPV) vaccine to prevent cervical cancer will be implemented from September 15 in Sindh, and health officials warn that the distrust of the community, persistent rumors and gaps in the training of vaccinators could undermine the campaign.

About 50% of the target group is registered in schools, with the current coordination [between health officials and the] Department of Education to facilitate vaccines at school, said Dr. Rean Baloch, speaking at the HPV seminar of Globe at the Aga Khan University (AKU).

“We have allocated around RS 200 million for the HPV vaccine, with the additional support of Gavi and other partners for promotion and dissemination,” he said, emphasizing the need for greater commitment to parents, teachers and medical care providers.

The campaign will depend on pediatricians, gynecologists and first -line workers to inform communities about HPV and cervical cancer prevention.

Photo courtesy: Aku

The director of the Immunization Project (EPI) of Sindh, Dr. Raj Kumar, described the deployment as a “historical initiative” and said the preparations focused on operational logistics and microplaning at the level of the Board of the Union, taking advantage of the experience of Sarpo, Tifoid and Polyomyelitis campaigns.

The authorities said that 20 million girls from nine to 14 years are registered in schools throughout the country, and the rest outside the school. It is estimated that 70% of vaccines will take place in schools and the rest will be administered in community environments through associations with public and private sectors.

What is HPV?

Cervical cancer kills more than 300,000 women worldwide every year, with the number of heavier deaths in low and medium -income countries. In Pakistan, the disease is among the main cancers in women is often diagnosed too late, despite being largely preventable through timely vaccination.

Human papilloma (HPV), a sexually transmitted infection, is responsible for 91% of cervical cancers worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 291 million women are diagnosed annually and approximately 340,000 die from the disease, most in countries like Pakistan.

Recent estimates indicate that every year in Pakistan, 5,008 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 3,197 die from the disease, according to human papilloma and related cancers, the information sheet 2023.

HPV has more than 200 known types, classified in low risk and high -risk categories. Although most low-risk infections are asymptomatic and are resolved on their own, HPV 16 and 18 high-risk strains are linked to 70-80% of cases of cervical cancer. In Pakistan, nine out of 10 cases are caused by these two strains. The country informs about 5,000 new cases and 3,000 deaths each year, with 73-74 million women at risk.

The HPV vaccine is more effective for girls from nine to 14 years, but coverage is hindered by data gaps, slow deployment and social barriers. The standardized incidence rate for the age of Pakistan is 6.1 per 100,000 women, above the recommended threshold of four or less. The WHO WHO strategy demands vaccination of 90% of girls in this age group by 2030, but global absorption remains less than 15% due to delays in national programs.

The zekoline vaccine that is introduced into Pakistan protects against HPV types 16 and 18, that the modeling of the International Cancer Research Agency (IARC) suggests that it could prevent up to 83% of cases of cervical cancer in the Eastern Mediterranean, Central, West and South of Asia. New generation vaccines that cover multiple types of HPV could increase 95%protection.

APPROACH TOBBER VS COMMITMENT LIVED BY THE COMMUNITY

The success of the HPV campaign in Sindh will depend not only on logistics but also on addressing deep social inequalities. A technical approach from top to bottom runs the risk of alienating the communities already excluded from decision -making, which underlines the need for participatory strategies that treat local populations as equal partners in health initiatives.

The entrenched health and education inequalities of Pakistan cannot be resolved only with technical solutions, he warned Dr. Kausar S Khan, a public health researcher and human rights activist, asking for participatory action research and participation directed by the community as the basis of social policy.

The policy and academic elite of the country (researchers, senior bureaucrats and service suppliers) form a small and privileged minority, while “the poor, women, minorities, transgender people and people with different sexual orientations” constitute the majority but remain excluded from decision making, Dr. Khan underlined.

“In Karachi, more than 50% of the population lives in Kachhi Abadis without water, electricity or sanitation, and yet we want to take science,” he said, warning that an upward approach, from top to bottom, ignores participatory ethics and local realities.

From his work in the participatory action investigation, Dr. Khan urged a “approach based on power and strength -based” that begins with “knowing themselves” and treating communities as equal partners instead of passive receptors of awareness campaigns by focusing on the Department of Women’s Development for HPV vaccination initiatives. This, he stressed, lacks the campaign.

However, the assumption that vaccines and other technical interventions can address deep social problems is incorrect.

“The successes we see are technical. But the social side is where it was,” he said, and emphasized that performance indicators and programmatic processes cannot replace the inclusion of the genuine community.

Gaps and conscience

The consciousness of cervical cancer and human papilloma (HPV) in Pakistan remains alarmingly low, with deep -rooted cultural norms and gender dynamics that poses important challenges for the absorption of the HPV vaccine, according to the results of the study of Jpegos Cahps presented by the social and behavior team of UNICEF (SBC).

The study found that only 17.2% of respondents knew cervical cancer, only 4.4% of caregivers had heard of HPV, and only 2.9% knew about the existence of the HPV vaccine. UNICEF officials said that fear of cancer could be a motivator, but the wrong concepts about hygiene, fatalistic beliefs and the limited role of women in making medical care decisions severely hinder acceptance.

It was discovered that language and framing influence perceptions: “vaccine” evoked the hope and prevention of adolescent girls, while “injection” triggered the fear of needles and diseases. UNICEF’s co-creation sessions emphasized portraying girls as aspiring issues instead of vulnerable objects, and the use of images that reflect real communities instead of idealized versions.

Consciousness about HPV vaccine is particularly low, and 95% of surveyed people have never heard of it. However, the confidence in the official orientation is high: 90% said they would accept the vaccine if recommended by the government, a doctor or religious leaders. Around 76–81% expressed interest in cervical cancer or HPV detection, and 79-80% said they would vaccinate themselves or their daughters.

Barriers include access to vaccines, family objections, minor fears about pain or side effects, cost concerns and shame due to erroneous concepts about the need for the vaccine. The reluctance is remarkably greater among mothers than daughters.

Mothers emerged as the key guardians for consent, due to their close communication with daughters, while parents, often not involved in daily health decisions, have passive approval that campaigns can stop.

“In fact, mothers who exhibited greater knowledge of cervical cancer showed more [bigger] Risk of not wanting to vaccinate their daughters compared to those who had never heard of it, “said Dr. Fyezah Jehan, professor and president of AKU.” It is confidence and tranquility, and addressing these concerns, which will allow us to handle it better. “

He added that acceptance is higher when mothers understand both the benefits and the safety of the vaccine, without having general concerns about child immunization.

UNICEF’s social listening efforts and other partners are underway to identify local concerns and adaptation communication strategies to generate vaccine confidence and avoid hesitation. The results indicate that both parents and health workers require a directed commitment.

“We need to convince our vaccinators, our health workers even more that this vaccine is good, and then they will transmit that trust … to the communities and the key interested parties,” said Dr. Paul Bloem, a senior technical officer of VPV Vaccine, emphasizing the need for continuous training to reinforce trust.

Despite the strong security data, rumors persist, particularly states that they link the vaccine with infertility. The Global Vaccine Safety Committee has repeatedly reviewed such accusations and has not found “any association between HPV vaccination and infertility.” Experts point out that the vaccine can actually help prevent infections that can reduce fertility.

The evidence of other countries, such as Bangladesh, shows that careful preparation and adoption of a strategy of a dose can achieve national coverage rates greater than 90% in the launch. Officials warn that without similar bases in Pakistan, achieving high coverage from the beginning, critical for long -term success, will remain out of reach.