The recent US action in Venezuela, in which President Nicolás Maduro was kidnapped in the United States to face criminal charges, has triggered a dramatic rupture not only in the geopolitics of the Western Hemisphere but also in the assumptions that have underpinned global sovereign lending for decades.

In Washington, the action was presented as a criminal law enforcement action; In Beijing and much of the Global South, it has been seen as an illegal overreach and weaponization of American power.

China’s reaction has been especially significant: rather than threatening military escalation, Beijing has framed its response in legal and diplomatic terms, signaling an aggressive defense of contracts, sovereign debt instruments and investment treaties. In doing so, China asserts that the future of geopolitical competition may be defined as much by law firms and arbitral tribunals as by aircraft carriers.

To understand why this matters, it is necessary to place the current standoff within the broader context of Chinese overseas loans and the legal frameworks on which they are based. Over the past two decades, China has become the largest lender to developing countries, largely through state policy banks and under the Belt and Road Initiative, which spans infrastructure, mining, energy and other strategic sectors in Asia, Africa, Latin America and beyond.

While authoritative global estimates vary, independent research has documented Chinese sovereign borrowing in the hundreds of billions and, by some accounts, more than $1 trillion in more than 100 countries. This debt is structured through bilateral agreements, commercial contracts and, in some cases, formal bilateral investment treaties (BITs).

Behind these agreements is a fundamental legal assumption: when a sovereign borrows money or grants concessions for projects, whether for a railway in Africa, a port in Southeast Asia or energy infrastructure in Latin America, successor governments will honor the obligations assumed by their predecessors.

This assumption is not simply a matter of accounting; it is a cornerstone of modern sovereign lending and investing. Creditors assess risk, investors commit capital, and contractors deploy resources based on the expectation that contracts and treaties will be respected through changes in political power. Both international financial institutions, private creditors and commercial lawyers depend on this continuity. When that assumption falls apart, the entire edifice of cross-border investment comes into question.

That is why China’s response to the operation in Venezuela is so revealing. Rather than responding with threats of force, which would be widely understood as escalation, Beijing’s public statements have emphasized the illegality of the US action under international law, principles of sovereignty, and basic norms of state conduct.

China’s Foreign Ministry condemned the operation as a violation of the UN Charter and basic norms of international relations, and called on the United States to respect Venezuela’s sovereignty, release its president and resolve disputes through negotiation and dialogue. These statements reflect a deliberate framing of the issue in legal terms.

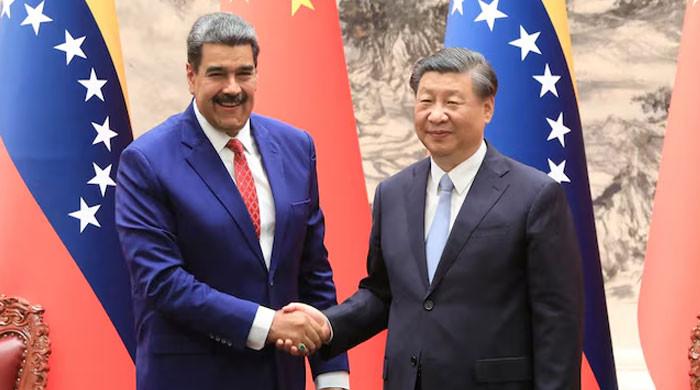

Crucially, recent events show that China and Venezuela had already been deepening their legal and economic ties. In late 2024, Venezuela ratified a bilateral investment treaty with China, which establishes protections such as fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, and most favored nation treatment for covered investments.

The treaty also prescribes mechanisms for resolving disputes, including through arbitration under specific international frameworks. Although China has not yet ratified the treaty, its existence illustrates a legal architecture that both sides have been building around their economic relationship.

This legal framework assumes a functioning sovereign Venezuelan government to which obligations can be attached. What happens, however, when that sovereign is violently removed from office at the behest of a rival power and subject to external legal processes unrelated to the underlying investments?

This is the scenario motivating the more dramatic claim circulating in some analytical circles that China is willing to wage a “lawyer war” by invoking investment treaties, international arbitration, and global legal institutions to defend its interests and impose legal costs on governments that fail to meet their commitments to Chinese creditors. In other words, China’s strategy may adopt the law itself as a geopolitical instrument.

At first glance, this might seem hyperbolic: how could legal claims equal the strategic weight of military force? The answer lies in the nature of China’s global exposure. Unlike traditional Western creditors, whose sovereign bonds are often issued under New York or London laws with clear enforcement mechanisms, China’s loans are much more diffuse, spread across jurisdictions with different legal capacities and often backed by project revenues, commodity deliveries or bilateral conventions.

The applicability of these obligations has always been uncertain.

If those obligations were suddenly repudiated by successor governments, particularly those aligned with US policy preferences after the regime change, the economic consequences for China’s creditors could be devastating. Defaults would pile up, infrastructure deals would fall apart and Chinese capital would risk losses on a scale that would dwarf any bilateral dispute. Legal action is a lever to avoid that result.

Viewed through this lens, China’s emphasis on legal norms and international adjudication does not simply refer to Venezuela; it is about protecting the institutional foundations of its global credit model. Treaty protections, arbitration forums, and bilateral investment agreements are mechanisms through which sovereign obligations can be enforced or at least negotiated when disputes arise.

If China can successfully bring lawsuits against a post-Maduro Venezuelan government or achieve recognition of its rights based on existing treaties, it would set a precedent affirming that sovereign debt and contracts cannot be nullified by outside intervention. That would reinforce the confidence of Chinese creditors and investors in the durability of their credits, mitigating the political risk that now seems existential.

This legal strategy also aligns with broader developments in China’s approach to dispute resolution. The country has been cultivating a network of domestic and international arbitration institutions capable of handling trade and investment disputes involving Chinese parties.

From the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) to the China International Commercial Court (CICC) and related bodies, these institutions provide spaces to resolve transnational disputes involving China. Although their reach and global acceptance are still evolving, they represent an expanding toolkit for legal statecraft under the Belt and Road Initiative.

However, there are limitations and countervailing forces worth recognizing. International arbitration and the application of investment treaties are highly controversial areas. Western legal institutions, such as those found in The Hague or under the auspices of the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), have historically been viewed with skepticism in China and other emerging powers, leading to alternative arrangements and hybrid mechanisms.

The enforcement of arbitral awards against sovereign States often depends on reciprocal legal frameworks and political will, rather than simple legal determination. In other words, securing a legal victory is one thing; implementing it is another. The political dimensions of this confrontation cannot be separated from the legal arguments either.

China’s official stance of non-intervention and respect for sovereignty is itself a strategic narrative that resonates throughout much of the Global South, where memories of colonialism and unilateral interventionism remain potent.

By framing its challenge to American behavior in terms of international law, China presents itself as a defender of a rules-based world order, even as it simultaneously seeks a web of bilateral agreements that serve its own strategic interests. This duality complicates Western efforts to present China’s growing influence solely in terms of debt dependence or coercive economics.

For the United States, the focus has been on immediate security and criminal justice concerns related to narcotics trafficking and international law enforcement. But Washington’s actions, unprecedented for its direct capture of a sitting head of state on foreign soil, challenge long-held assumptions about sovereign conduct and invite reaction from countries that see their own investments and legal claims in jeopardy. If U.S. policy supports the idea that outside intervention can restore a country’s legal obligations, the implications for global sovereign contracts could be profound.

The narrative that China is “declaring war on lawyers” is more than a rhetorical flourish; captures a deeper shift in the tools of global competition. Military power and traditional geopolitics are important, but so are legal rules, treaty rights, and the enforceability of agreements that bind sovereign states to external obligations. China’s response to the Venezuela crisis illustrates how law has become a field of strategic dispute, a field where contracts, arbitration and investment protection can shape the calculus of power in the 21st century.

As geopolitical rivalry intensifies, the question of who writes the rules and who can enforce them will be at the center of the global order. And in that contest, legal strategy can be, in fact, one of the most important instruments of statecraft.

The author is a trade facilitation expert and works with the federal government of Pakistan.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of PakGazette.tv.

Originally published in The News