Karachi:

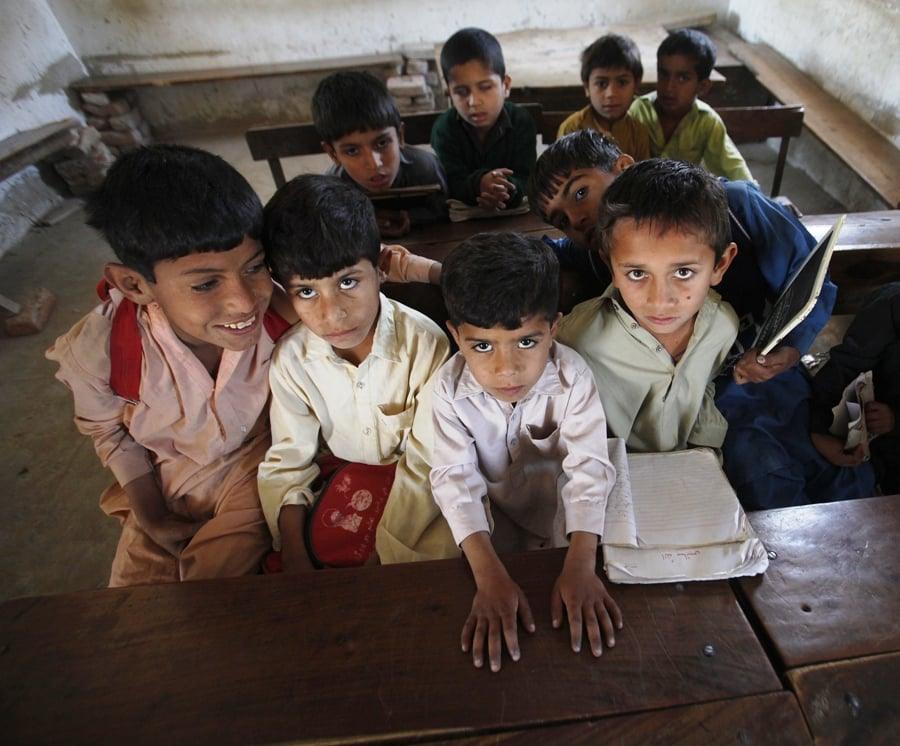

In South Asia, the climate crisis has made monsoons fiercer, heat waves more severe and floods more relentless, transforming nature’s wrath from a distant threat into an immediate reality that is reshaping landscapes, disrupting lives and deepens vulnerabilities across a wide range of human concerns, including education.

According to a recent UNICEF analysis, in 2024, almost half of the quarter-billion students in 85 countries who faced climate-induced disruptions to their education were from this region, which now bears the brunt of worsening shocks. environmental. The impact on education, as documented by the UN agency, was staggering, with India topping the list at 54.78 million children facing academic disruption, followed by 35.38 million in Bangladesh, 26.23 million in Pakistan and 10.91 million in Afghanistan. . The region’s fragile education systems collapsed under the weight of the heat intensifiers, which became the largest driver of school closures around the world.

In total, the climate events affected some 242 million students globally, from pre-primary to upper secondary education, with 128 million in South Asia, where most disruptions occurred. UNICEF data reveals that more than 118 million students were affected by heat waves in April alone, making it the peak month for weather-related school closures in India, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Pakistan. By May, temperatures in parts of South Asia had soared to 47 degrees Celsius, further exacerbating the crisis.

common crisis

Despite the shared threat of climate change, South Asian nations have largely faced natural disasters in isolation, each grappling with the consequences independently. While extreme weather indiscriminately devastated the region, a fragmented response has deepened the vulnerabilities of those most affected. Heat waves dominated South Asia’s climate crises, but intermittent flooding and storms compounded the devastation, leaving countless schools inaccessible. In India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, where millions of children were already out of school, the situation was particularly serious. UNICEF has warned of cascading consequences, emphasizing that wasting time in the classroom often leads to long-term setbacks for rural and underserved communities.

For Pakistan, a country on the frontlines of the climate crisis, political instability may have changed policymakers’ approach to addressing the pressing issue. “Addressing climate change effectively requires policy consistency and the allocation of necessary funds to long-term mitigation and adaptation programs,” said Hassan Akbar, Pakistan Fellow at the Wilson Center. Political instability in Pakistan, he warned, has diverted daily attention from existential challenges such as climate change and the continuity of disrupted politics. “As South Asia faces extreme weather events as a shared challenge, the lack of regional cooperation and action on climate change leaves the region less resilient,” Akbar added.

Looking to the future

In its analysis titled ‘Learning Disrupted: A Global Snapshot of Climate-Related School Disruptions,’ the UN agency urged governments to prioritize building and modernizing schools to withstand extreme weather, with improvements such as ventilation improved, solar-powered cooling systems and infrastructure Designed to withstand floods and storms. He also recommended integrating climate change education into national curricula, empowering students to better understand and address future challenges. Additionally, the agency emphasized the need for robust data collection systems to track the impact of climate risks on education, arguing that such systems would help policymakers better understand and mitigate disruptions.

When asked about challenges across the region, Akbar noted: “One of the biggest obstacles is the lack of data sharing, which hampers both early warning systems and long-term scientific research into how the ecosystem is evolving. shared in the region”.

As the world grapples with the compounding effects of climate change and educational disruption, Pia Rebello Britto, UNICEF global director of adolescent education and development, warned that addressing both simultaneously is crucial. Despite the bleak outlook, the UN agency stressed that solutions are within reach but must be urgently scaled back.