We are living a technological change unlike anyone in history. As artificial and robotic intelligence quickly evolve, they are doing more than changing the way we work, they are changing because We work. During the next decade, if humanity can share automation technology evenly throughout society, we face the real possibility that most people simply need to work to survive. Some futurists, including myself, call this the automated abundance economy.

The basic idea is simple: once machines can do most of the works, such as agriculture, construction, medical care, education, the essential elements of life can occur in abundance, with very little human work. In that world, wealth ceases to be the reward for work and becomes a shared result of automation.

In the heart of this change there are two forces: almost total automation and a proposed universal basic income (UBI). The machines and software are improving, faster and more cheaper, and are already replacing some mass jobs, from factory floors to fast food counter. Probably within five years, machines will routinely build our homes, cultivate our food, teach our children and take care of the elderly. This type of productivity will generate immense wealth, even if humans no longer create it directly.

So how do we make sure wealth benefits everyone? That’s where Ubi enters. It is not well -being, it is a dividend. A part of the value created by automation, distributed to all citizens simply because they are part of the system that led to this exact economy.

Critics will say that this is socialism, but it is not. The automated abundance economy still supports private property, entrepreneurship and innovation. People who invest in automation will see yields. But the system would also be taxed or regulated so that a part of that wealth returns to the public in the form of UBI, options on AI companies or similar ideas.

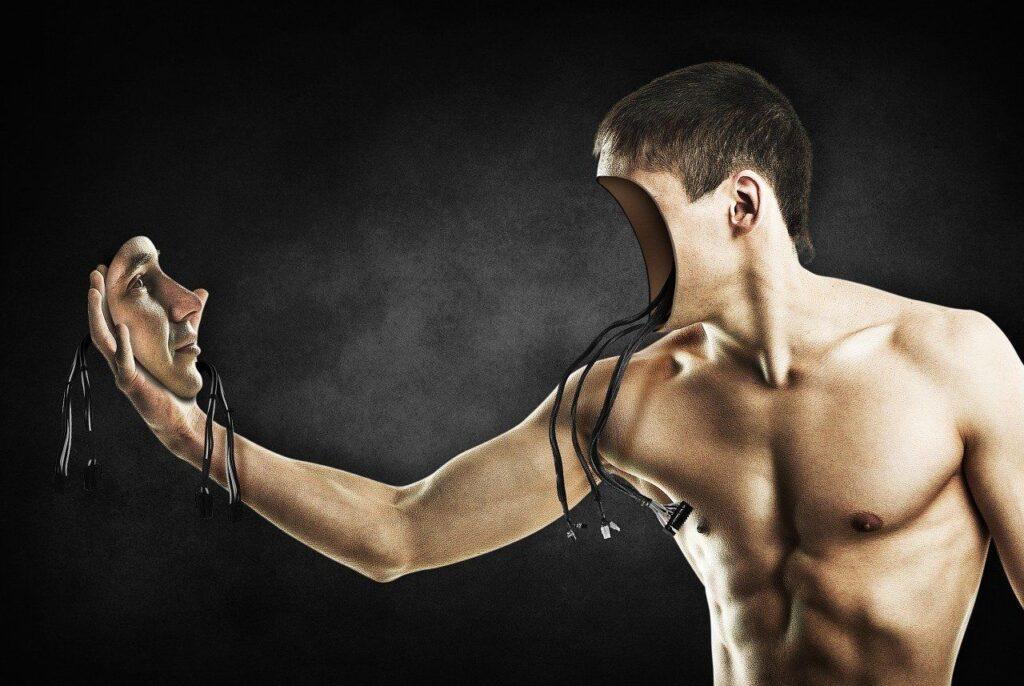

In this context, UBI and other social monetary programs become a kind of economic citizenship, a guarantee that it will have access to food, shelters, medical care and education, without having to hit a clock. It also challenges the old idea that the value of a person is linked to their work. In this future, we all have an intrinsic economic value just being alive.

Of course, although work will not be a requirement for survival, many people willpower He still chooses to work. But in this new system, motivation will be intrinsic, not economical. Creative fields, concert work, writing, design: these will flourish. And since survival is not at stake, people can afford to take risks, experiment or fail without fear.

Some parts of this are already happening. Automation is constantly pushing humans of repetitive and manual works. The automated abundance economy simply follows that tendency to its logical conclusion. Because when machines can handle everything, from cleaning to care, it forces us to ask: what do we want to do with our time, if survival no longer demands most of them?

The answer could be a global cultural rebirth. A world where creativity, curiosity and connection define daily life; A world where everyone has the opportunity to be a manufacturer, thinker or explorer. Finally, we can have the time and freedom to completely explore human potential, no longer bogged down by daily routine.

The automated abundance economy is not just about work either. Futurists like me want the government to give or rent a humanoid robot to all US homes. These robots would handle everyday tasks, such as cooking, cleaning and washing clothes, saving hours every week for families. Over time, having a personal robot could be as normal as being the owner of a smartphone today.

Even governance could evolve. If machines can enforce security, compliance and even legal standards, we may not need so much traditional bureaucracy. Public systems could be administered by transparent trained in ethical frameworks and made up of citizens. Some even suggest models such as liquid democracy, where people vote directly on policies, feeding those preferences in smart systems that execute decisions.

What I like most about the automated abundance economy is that it avoids the worst of both capitalism and socialism. It is not intended to destroy markets or prohibit private property. Instead, he keeps innovation alive while making sure no one stays behind.

Even so, none of this will be easy. If we are not careful, automation could concentrate wealth and power even more. Surveillance, labor displacement and cultural reaction are real risks. Only engineers cannot shape this future: we will need ethics, artists, policy formulators and common people at the decision table. It has to be ethical, inclusive and democratic.

We like it or not, the automated abundance economy is coming much faster than most people believe. Our task is not to fight the future: it is to guide it, to shape a society where freedom, compliance and human dignity are not only reserved for the lucky few. This is not just a new type of economy; It is a new way of life, a society should adopt.