Plasma rashes that accumulate with each other, the solar wind that extends with exquisite details: the closest images of our sun are a gold mine for scientists.

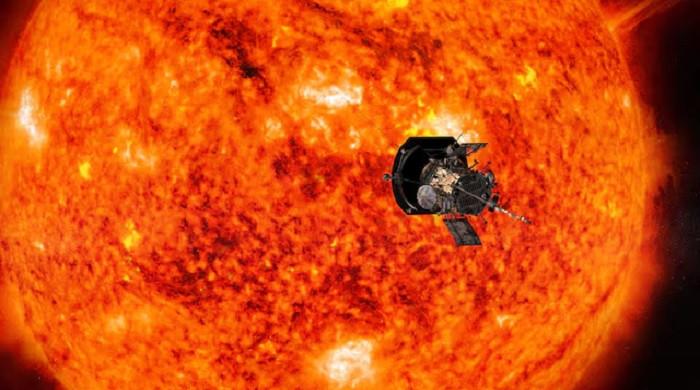

Captured by the Parker solar probe during its closest approach to our star as of December 24, 2024, the images were recently thrown by NASA and are expected to deepen our understanding of the space climate and help protect against solar threats to the earth.

A historical achievement

“We have been waiting for this moment since the end of the fifties,” said the mission project scientist at the Johns Hopkins applied physics laboratory, he said AFP.

The previous spacecraft has studied the sun, but from much farther.

Parker was launched in 2018 and is named after the late physical Eugene Parker, who in 1958 theorized the existence of the solar wind, a constant current of electrically charged particles that fuev through the solar system.

The probe recently entered its final orbit, where its closest approach takes it to only 3.8 million miles from the surface of the sun, a milestone achieved for the first time on the eve of Christmas 2024 and is repeated twice from an 88 -day cycle.

To put the proximity in perspective: if the distance between the earth and the sun was measured in one foot, Parker would be only half an inch away.

Its heat shield was designed to support up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,370 degrees Celsius), but for the delight of the equipment, it has only experienced around 2,000 ° F (1090c) so far, revealing the limits of theoretical modeling.

Surprisingly, the instruments of the probe, only a patio (meter) behind the shield, remain little more than room temperature.

Looking at the sun

The spacecraft carries a single summary, the wide field field images for the solar probe (WISPR), which captured data while Parker sank through the Sun Crown or the outer atmosphere.

Sides in a second video, the new images reveal executions of coronal mass (CMEs), massive gusts of charged particles that drive the space climate, in high resolution for the first time.

“We had multiple CME that accumulate one on top of the other, which is what makes them so special,” said Rawafi. “It is really surprising to see that this dynamic happens there.”

Such eruptions triggered the generalized auroras seen in much of the world last May, since the sun reached the peak of its 11 -year cycle.

Another surprising feature is how the solar wind, which flows from the left of the image, draws a structure called the heliospheric current sheet: an invisible limit where the magnetic field of the sun turns from north to south.

It extends through the solar system in the form of a rotating skirt and is essential to study, since it governs how solar eruptions propagate and how strongly the earth can affect.

Why does it matter

The space climate can have serious consequences, such as overwhelming electrical networks, communications interruptions and threatening satellites.

As thousands of more satellites enter the orbit in the coming years, track them and avoid collisions will be increasingly difficult, especially during solar disturbances, which can make the spacecraft slightly move from its planned orbits.

Rawafi is particularly excited about what is coming, since the sun goes towards the minimum of its cycle, it is expected in five to six years.

Historically, some of the most extreme space weather events have occurred during this decline phase, including the infamous Halloween solar storms of 2003, which forced astronauts aboard the International Space Station to take refuge in a more protected area.

“Capture some of these great and great rashes … It would be a dream,” he said.

Parker still has much fuel than engineers initially expected and could continue to function for decades, until their solar panels degrade to the point where they can no longer generate enough energy to maintain the spacecraft properly oriented.

When his mission finally ends, the investigation will disintegrate slowly, becoming, in Rawafi’s words, “part of the solar wind itself.”