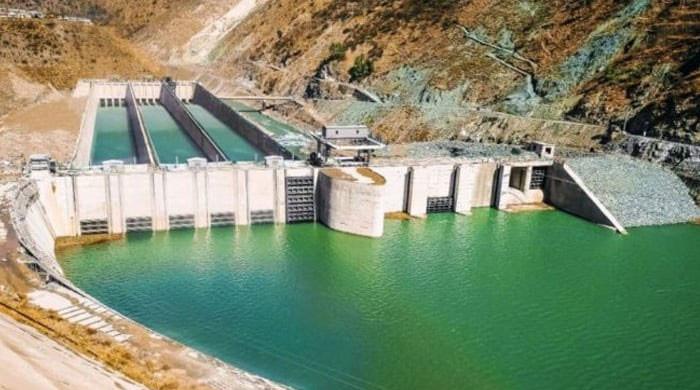

After years of drought, the 2025 monsoon brought abundance. Pakistan’s reservoirs were full. Tarbela, Mangla and Chashma were almost full at the beginning of Kharif.

However, the Indus River System Authority announced a shortage of 8% for the Rabi season. The contradiction, full reservoirs and still shortages, reveals the true water crisis in Pakistan. The problem is not scarcity but mismanagement. This is a crisis of governance, not hydrology, and arises from the unfulfilled promise of the 1991 Water Sharing Agreement.

When the four provincial premiers signed the agreement 34 years ago, they were designing a national strategy for water security. The document established a framework for Indus Basin management through six linked principles: fair allocations, surplus distribution, storage development, ecological protection, provincial autonomy and operational discipline. The framers understood that while rivers would rise and fall, institutions could bring stability through predictable rules and shared responsibility.

Clause 2. Fixed provincial participations. Clause 4 sets out rules for sharing surplus water. Clause 6 required new deposits. Clause 7 recognized the importance of environmental flows in protecting the Sindh Delta. Clauses 8 to 12 gave provinces freedom to develop their own water resources. And Clause 14(c) made irrigation the highest operational priority, stating that “existing reservoirs would be operated with priority for the irrigation uses of the provinces.” Food had to come before energy generation.

But over the years, only Clause 2, the allocation table, has remained in the spotlight, often the cause of inter-provincial friction. The rest is ignored. No major reservoirs have been built since Tarbela, and total storage capacity has fallen from about 20 maf (million acre-feet) to about 13.5 maf. Without additional storage, excess floodwater cannot be captured or shared. Clause 4, intended to distribute abundance, remains inactive.

The clause 7 commitment to the delta has been ignored. The flows below Kotri have decreased from about 50 maf in the late 20th century to less than 20 maf today, and that too mainly in Kharif. In most parts of Rabi, the Indus below Kotri dries up. Salt water invades mangroves and farmland, displacing fishing communities and turning one of South Asia’s richest ecosystems into a wasteland.

Clause 14(c), which guarantees irrigation priority, has not achieved better results. Tarbela tunnels and outlets are largely powered by hydroelectric programmes. In large tunnel works, the full capacity of the dam cannot be released, even when it is full. In 2024-25, limitations of Tarbela’s low-level outlets limited IRSA’s access to deep storage. Last year, similar operational constraints helped turn a projected 16% to 18% shortage into more acute impacts than the headline numbers suggested, a pattern that threatens to repeat itself. Reservoirs are full as farmers at the ends of the canal wait for water. This directly violates the intent of the Agreement. When irrigation priority is reversed, food security is put at risk.

An 8% deficit in Rabi may seem small, but its consequences are serious. Wheat grown this season feeds 250 million Pakistanis. An irrigation deficit at planting time means lower yields, higher prices and tighter food supplies months later. The system is technically capable of avoiding this outcome, but is not governed to do so. Full dams have become symbols of abundance that hide management failures.

Pakistan does not suffer from lack of water. It suffers from poor governance and insufficient implementation. The 1991 Agreement provided a comprehensive framework that, if followed, would have balanced competing needs and reduced the cycle of floods and droughts. The agreement gave the provinces significant autonomy: Punjab and KP could build small dams of less than 5,000 acres without federal approval; Balochistan could develop the right bank independently; Provinces could modernize canal networks with lined canals and precision irrigation to further expand their allocations.

However, this freedom has largely gone unused. Provincial governments have focused on demanding more water from the system rather than developing what they already have the right to develop independently. None of these mechanisms were activated together. The system was reduced to paper assignments without the development architecture to make those assignments viable.

The pattern repeats itself every year. Monsoon floods fill the dams, but much of the unused water flows out to sea. In winter, admissions decrease and the system announces shortages. Each cycle deepens provincial mistrust and erodes confidence in federal coordination. The agreement sought to avoid this by institutionalizing cooperation rather than crisis management. It offered a path from “not enough water” to “not enough governance.” And governance can be fixed.

Implementing the spirit of the agreement now requires more political will than engineering skill. The framework already exists. What is needed is compliance. The Common Interest Council should reaffirm the priority of irrigation under Clause 14(c) and empower IRSA with operational supervision over discharges from the Wapda reservoir, ending the disconnect between allocation authority and operational control.

Federal and provincial governments must accelerate storage projects to recover capacity lost to sedimentation. There is a need to restore ecological flows downstream of Kotri. Provincial irrigation departments must invest in small dams, canal modernization and efficient irrigation within their allocations. Real-time data on inputs and emissions must be made public so that transparency replaces suspicion.

This year’s monsoons have given Pakistan an opportunity. Nature has done its part by filling the reservoirs. The question is whether governance will do its thing. If the deal is treated as a living framework rather than a relic, this Rabi season could mark a turning point. Three decades of experience have shown that Pakistan’s challenge is not how much water flows through its rivers but how it is managed. The agreement endures because it was based on consensus. That same consensus must now be used to implement it.

If Pakistan implements the agreement as designed, this year of flooding could become the foundation for long-term stability. Otherwise, full reservoirs will once again produce empty canals, and the country will learn once again that its true shortage is not of water but of governance.

The author is a former irrigation and finance minister of Punjab, with extensive experience in the provincial and federal legislatures of Pakistan.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of PakGazette.tv.

Originally published in The News